Context is King: The Software Engineer’s Guide to LLM Prompt Engineering

How system prompts, user instructions, and skill files orchestrate the intelligence behind every LLM interaction

The Illusion of the Magic Prompt

You’ve probably been there. You craft what feels like the perfect prompt, hit enter, and the LLM returns something brilliant. Then you try the same approach on a slightly different task and get garbage. What changed?

The uncomfortable truth is that your “perfect prompt” was never the whole story. What looked like linguistic alchemy was actually the result of a complex interplay between your words and everything else the model could see at that moment—its entire context window.

This realization has fundamentally shifted how serious practitioners think about working with LLMs. As Andrej Karpathy put it in his now-famous declaration: “People associate prompts with short task descriptions you’d give an LLM in your day-to-day use. When in every industrial-strength LLM app, context engineering is the delicate art and science of filling the context window with just the right information for the next step.”

The prompt is important. But it’s only one actor on a much larger stage.

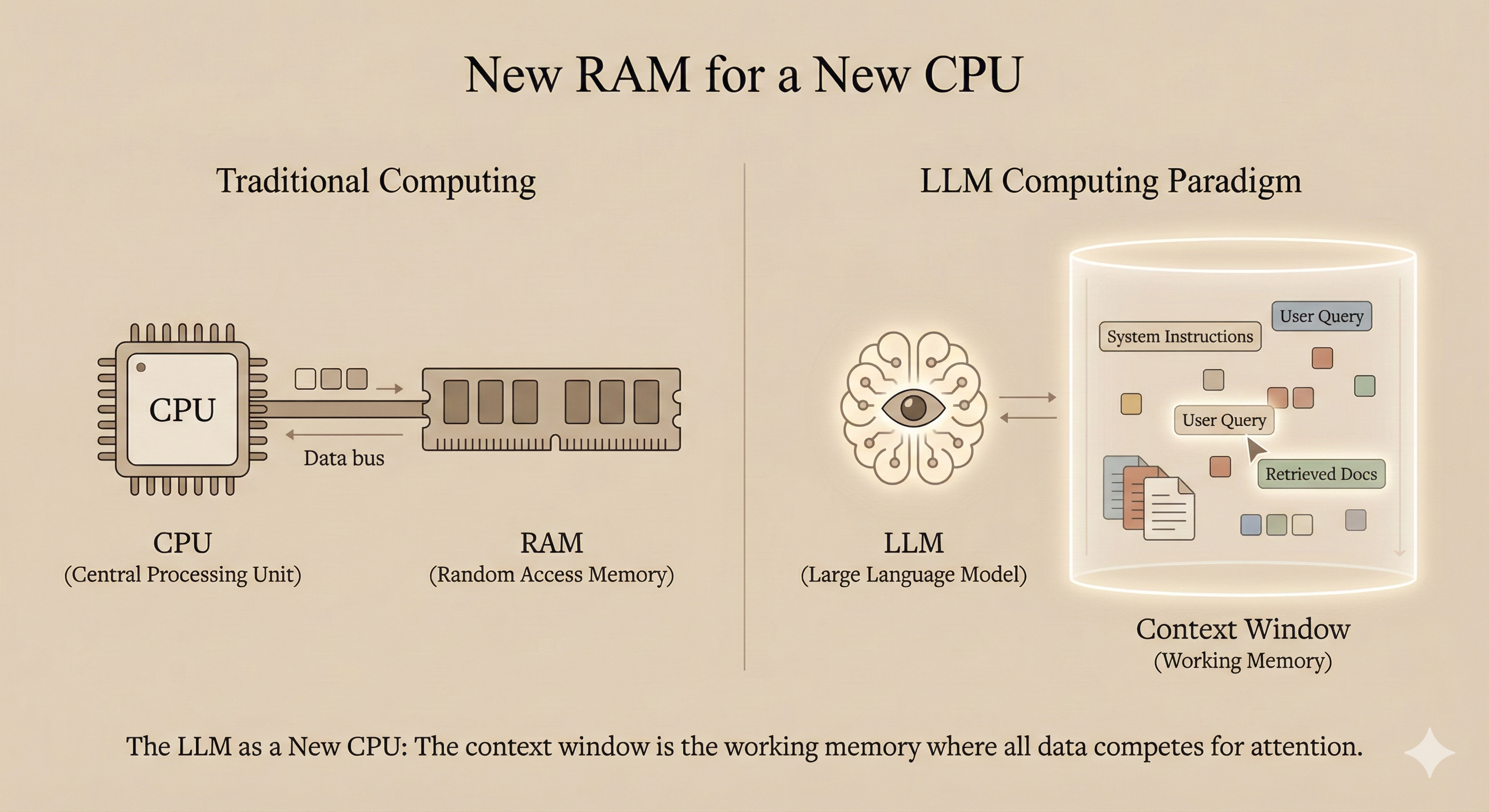

Understanding the Context Window: RAM for a New Kind of CPU

To understand why context matters so much, you need to understand what an LLM actually “sees” when it generates a response.

Karpathy offers a useful mental model: think of the LLM as a new kind of CPU, and its context window as the RAM—the model’s working memory. Every token fed into that window competes for the model’s attention budget. Your job as the engineer is like that of an operating system: load that working memory with precisely the right code and data for the task at hand.

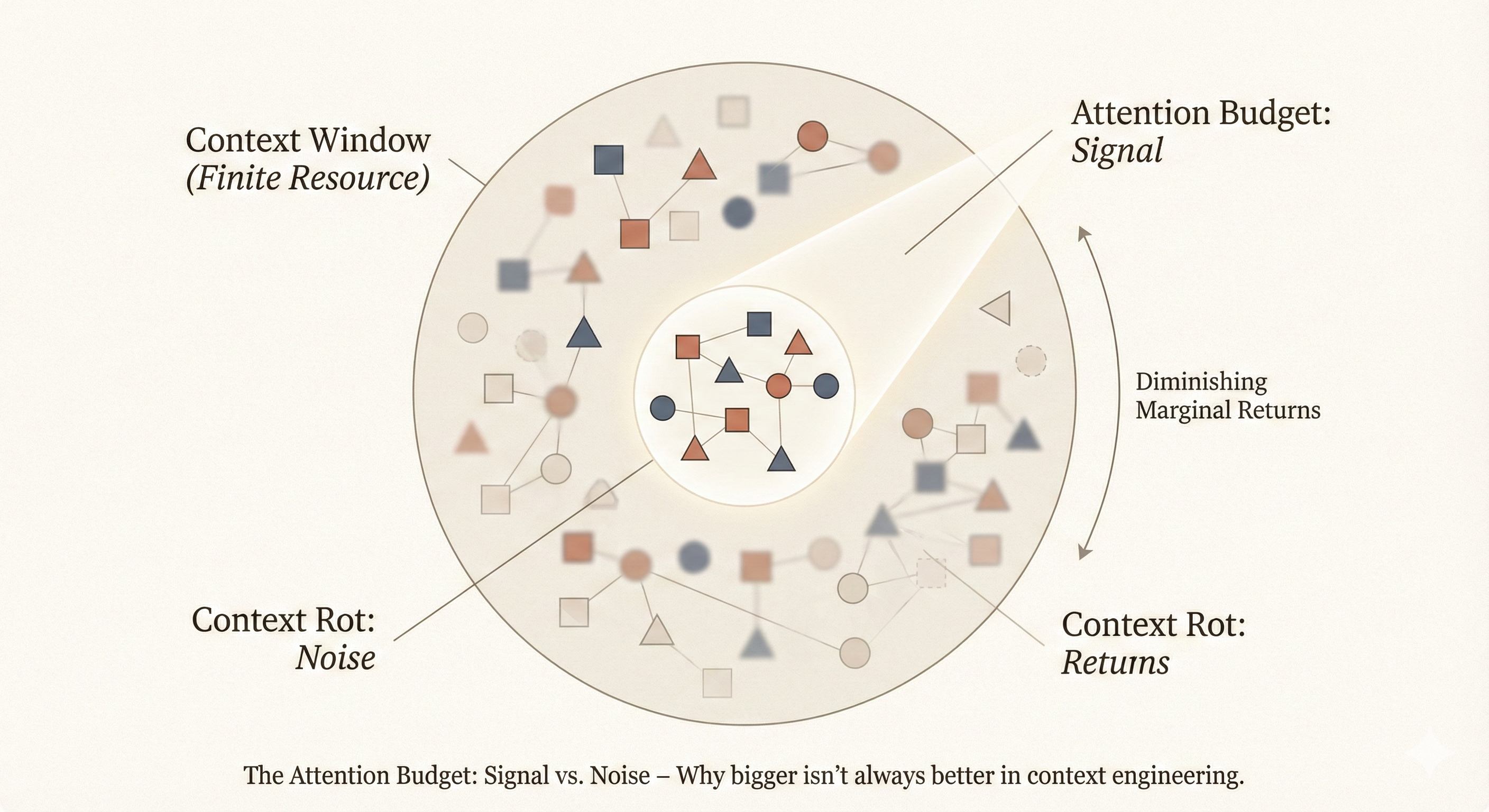

This context window has hard limits. Current models range from around 128K tokens to over 1 million tokens for frontier models like GPT-4.1. But here’s the critical insight: bigger isn’t necessarily better. Research on “needle-in-a-haystack” benchmarks has revealed a phenomenon called context rot—as the number of tokens in the context window increases, the model’s ability to accurately recall information from that context decreases. (See Chroma’s research on context rot for detailed analysis.)

Context, therefore, must be treated as a finite resource with diminishing marginal returns. As Anthropic’s engineering team explains: “Like humans, who have limited working memory capacity, LLMs have an ‘attention budget’ that they draw on when parsing large volumes of context.”

Good engineering means finding the smallest possible set of high-signal tokens that maximize the likelihood of your desired outcome.

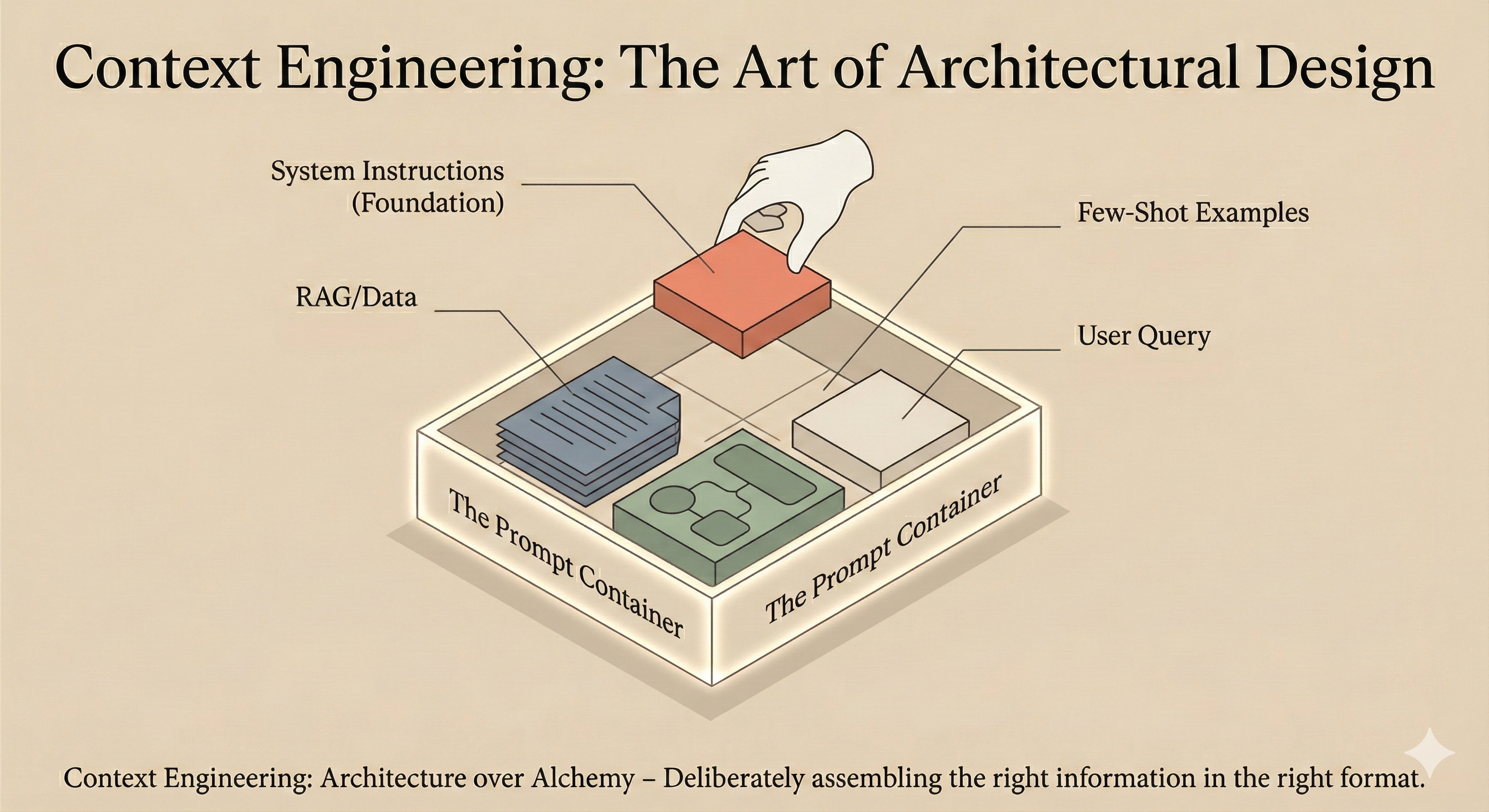

The Anatomy of a Modern LLM Request

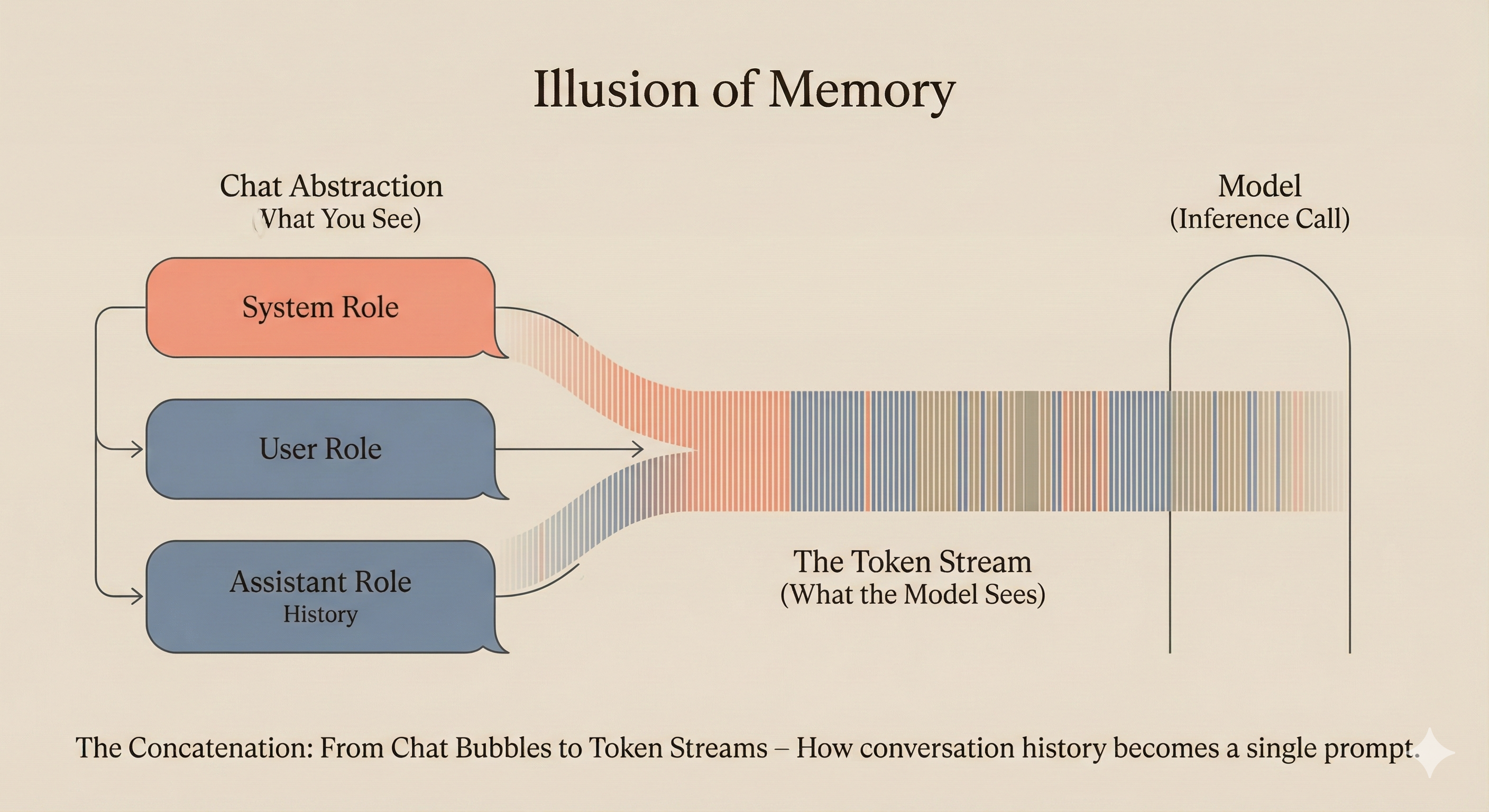

When you interact with an LLM through a chat interface or API, you’re not sending a single string of text. You’re sending a structured message array with distinct roles, each serving a specific purpose in shaping the model’s behavior.

The Three Fundamental Roles

System Role: This sets the high-level context and behavioral guidelines. It’s typically the first message the model processes and establishes persistent instructions for the entire conversation. Think of it as the model’s “job description”—defining who it is, how it should behave, and what constraints it must follow.

User Role: This contains the actual requests or queries from the human. It’s where specific tasks, questions, and contextual information for the immediate interaction live.

Assistant Role: This holds previous responses from the model itself. In multi-turn conversations, these create continuity and allow the model to build on its prior output.

In more advanced agentic systems, additional roles emerge—tool_use, tool_result, and planner—to organize reasoning, tool invocation, and decision-making. But the fundamental system/user/assistant triad remains the backbone of LLM interaction architecture.

The Hidden Reality: It’s All Just Tokens

Here’s something crucial to understand: the model doesn’t “remember” conversations. Every single time you send a message, all the conversation history is concatenated into a single prompt string with special tokens marking role transitions.

When you chat with Claude and it seems to remember your earlier questions, what’s actually happening is that the entire conversation—system prompt, all user messages, all assistant responses—is being fed into the context window as one continuous sequence. The chat interface is an abstraction. Under the hood, it’s always a single inference call on a carefully constructed token stream.

As the Hugging Face Agents Course explains: “The model does not ‘remember’ the conversation: it reads it in full every time.”

This is why the system prompt’s position matters. It’s not just configuration—it’s the first content the model sees when processing every single request.

How LLM Providers Structure System Prompts

Different providers have evolved different approaches to system prompt architecture, but common patterns have emerged across the industry.

OpenAI’s Approach

OpenAI’s GPT-4.1 and GPT-5 models are trained to follow instructions more closely and literally than their predecessors. According to their GPT-4.1 Prompting Guide, these models are “highly steerable and responsive to well-specified prompts.”

Their recommended structure follows a clear hierarchy:

- Concise instruction describing the task (first line, no section header)

- Additional details as needed

- Optional sections with headings for detailed steps

- Examples (optional, but powerful)

- Notes on edge cases and specific considerations

OpenAI’s guidance emphasizes that “if model behavior is different from what you expect, a single sentence firmly and unequivocally clarifying your desired behavior is almost always sufficient to steer the model on course.”

Anthropic’s Approach

Anthropic structures Claude’s system prompts with what they call “the right altitude”—the Goldilocks zone between two failure modes. As they explain in their context engineering guide:

“At one extreme, we see engineers hardcoding complex, brittle logic in their prompts to elicit exact agentic behavior. This approach creates fragility and increases maintenance complexity over time. At the other extreme, engineers sometimes provide vague, high-level guidance that fails to give the LLM concrete signals for desired outputs or falsely assumes shared context.”

Anthropic’s production system prompts include:

- Product information and capabilities

- Behavioral guidelines and refusal handling

- Tone and formatting instructions

- User wellbeing considerations

- Knowledge cutoff information

- Tool definitions and usage patterns

- Memory system instructions

One notable pattern: Anthropic heavily uses XML tags to structure their prompts. This isn’t arbitrary—Claude was trained with XML tags in the training data, making them particularly effective delimiters for organizing complex instructions.

Google’s Approach

Google’s Agent Development Kit (ADK) introduces a sophisticated “context architecture” that separates storage from presentation. According to their Google Developers Blog post on context-aware multi-agent frameworks, they distinguish between durable state (sessions) and per-call views (working context), allowing storage schemas and prompt formats to evolve independently.

Their framework emphasizes explicit transformations—context is built through named, ordered processors rather than ad-hoc string concatenation. This makes the “compilation” step observable and testable.

The Lifecycle of a User Prompt: With and Without Engineering

Let’s trace what happens when a user types “Help me write a function to parse JSON” into two different systems.

Scenario A: Raw, Unengineered Request

The user’s message goes directly to the model API with minimal wrapping:

messages: [

{ role: "user", content: "Help me write a function to parse JSON" }

]

What the model sees: A single, context-free request. The model must infer:

- What programming language?

- What level of error handling?

- What input/output format?

- Should it explain the code or just provide it?

- What edge cases matter?

What happens: The model draws on its training to make reasonable assumptions. You might get Python (it’s common), basic error handling, and a general-purpose solution. Or you might get JavaScript. Or something else entirely. The output quality depends heavily on what the model’s training data suggests is a “typical” response to such requests.

Scenario B: Engineered Context

The same request, but now with proper context engineering:

messages: [

{

role: "system",

content: "You are a senior TypeScript developer at a fintech company.

You write production-quality code with comprehensive error handling,

type safety, and clear documentation. You follow the company's coding

standards: use functional programming patterns, avoid any, and include

JSDoc comments. When writing code, consider edge cases common in

financial data: null values, malformed data, and type coercion issues."

},

{

role: "user",

content: "Help me write a function to parse JSON from our payment

processor's webhook. The data sometimes comes with numeric strings

instead of numbers for amounts. Here's a sample payload:

{\"transaction_id\": \"tx_123\", \"amount\": \"99.99\", \"status\": \"completed\"}"

}

]

What the model sees: A rich context with clear signals about:

- Language and paradigm (TypeScript, functional)

- Quality expectations (production-ready, typed, documented)

- Domain context (fintech, payment processing)

- Specific challenge (type coercion issues)

- Concrete example to work from

What happens: The model generates TypeScript with proper types, handles the string-to-number conversion explicitly, includes null checks appropriate for webhook data, and documents the function according to the specified standards. The output is immediately usable because the context eliminated ambiguity before generation began.

The difference isn’t that the model “got smarter” in Scenario B. It’s that we gave it the information it needed to make informed decisions.

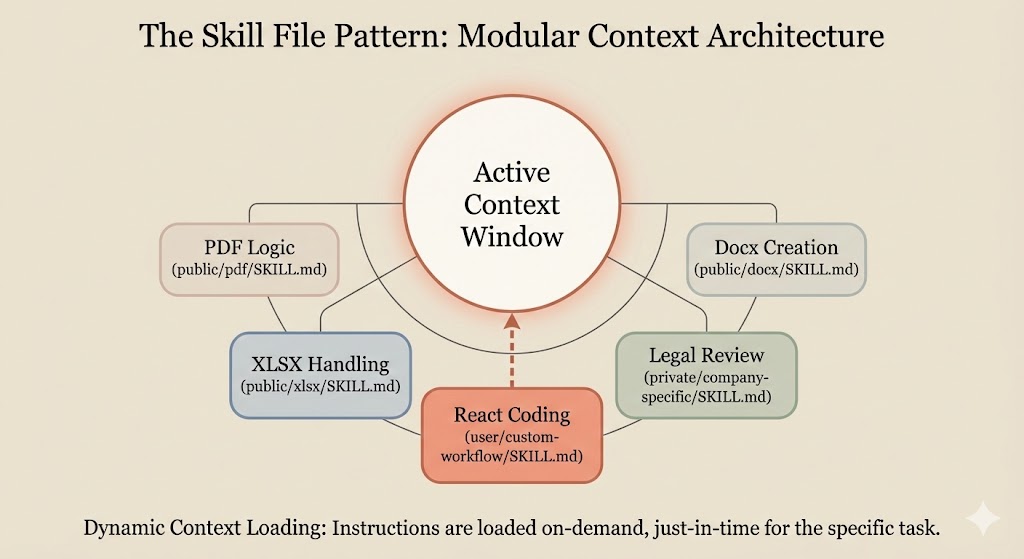

The Skill File Pattern: Modular Context Architecture

One of the most powerful patterns emerging in production LLM systems is the concept of “skills”—modular context files that can be loaded dynamically based on task requirements.

Anthropic’s internal architecture reveals this pattern clearly. They maintain skill directories containing SKILL.md files with specialized instructions for different task types: document creation, spreadsheet manipulation, PDF handling, frontend design, and more.

The pattern works like this:

- Discovery: The agent preloads names and descriptions of installed skills into the system prompt

- On-demand loading: Claude only reads full skill content when a matching task is detected

- Composability: Complex tasks can reference multiple skill files

/mnt/skills/

├── public/

│ ├── docx/SKILL.md

│ ├── pdf/SKILL.md

│ ├── xlsx/SKILL.md

│ └── pptx/SKILL.md

├── private/

│ └── company-specific/SKILL.md

└── user/

└── custom-workflow/SKILL.md

This architecture solves a fundamental tension: you want the model to have access to detailed instructions for any task it might encounter, but you can’t load everything into the context window at once without hitting token limits and triggering context rot.

Skills provide just-in-time context loading—the model reads the detailed instructions only when it determines they’re relevant to the current task. This is context engineering at its most practical.

State of the Art: Best Practices from Providers and Thought Leaders

After reviewing technical documentation, research papers, and guidance from major providers, several principles emerge consistently.

1. Be Explicit About What You Want

GPT-4.1, Claude 4.x, and other modern models are trained for precise instruction following. This is a double-edged sword—they do what you say, not what you mean.

Anthropic’s guidance (from their Claude 4 best practices): “Customers who desire the ‘above and beyond’ behavior from previous Claude models might need to more explicitly request these behaviors with newer models.”

OpenAI’s guidance (from their GPT-4.1 Prompting Guide): “If model behavior is different from what you expect, a single sentence firmly and unequivocally clarifying your desired behavior is almost always sufficient to steer the model on course.”

The era of hoping the model will figure out what you really wanted is over. State it directly.

2. Explain Why, Not Just What

Modern models respond better when they understand the motivation behind instructions. This isn’t anthropomorphizing—it’s practical engineering. Anthropic’s documentation specifically notes that “providing context or motivation behind your instructions, such as explaining to Claude why such behavior is important, can help Claude 4.x models better understand your goals and deliver more targeted responses.”

# Less effective

"Format responses as bullet points."

# More effective

"Format responses as bullet points because this output will be displayed

in a mobile UI where long paragraphs are difficult to read."

The reasoning gives the model additional signal for edge cases you didn’t explicitly specify.

3. Use Examples Strategically

Few-shot prompting remains one of the most reliable techniques for shaping output. But examples need to be chosen carefully:

- Include challenging cases and edge cases

- Show both positive examples (what to do) and negative examples (what not to do)

- Make examples representative of real variation in your data

Anthropic specifically notes in their context engineering guide: “Negative examples are extremely important—they define the boundaries of the feature and ensure it doesn’t over-trigger.”

4. Treat Context as a Scarce Resource

Even with million-token context windows, more isn’t always better. The goal is the minimum necessary context for optimal performance.

Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke’s formulation (from his original tweet): Context engineering is “the art of providing all the context for the task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.”

Note the word “plausibly”—not “every possible piece of information,” but what’s actually needed for the task.

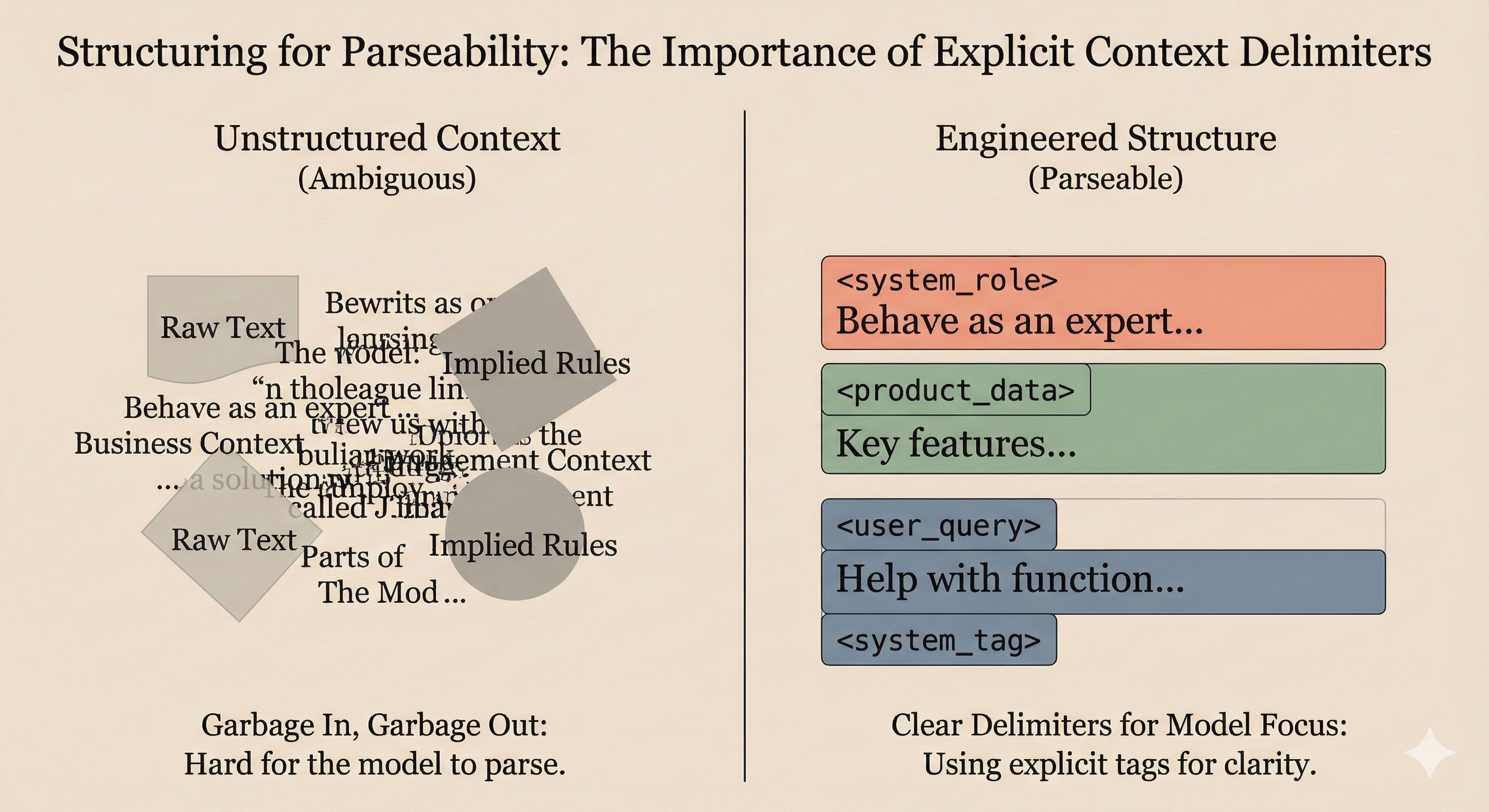

5. Structure for Parseability

Both OpenAI and Anthropic recommend clear delimiters for different sections of context. OpenAI suggests XML, Markdown, or JSON depending on content type. Anthropic heavily uses XML tags.

The key insight from OpenAI’s guide: “Use your judgement and think about what will provide clear information and ‘stand out’ to the model. For example, if you’re retrieving documents that contain lots of XML, an XML-based delimiter will likely be less effective.”

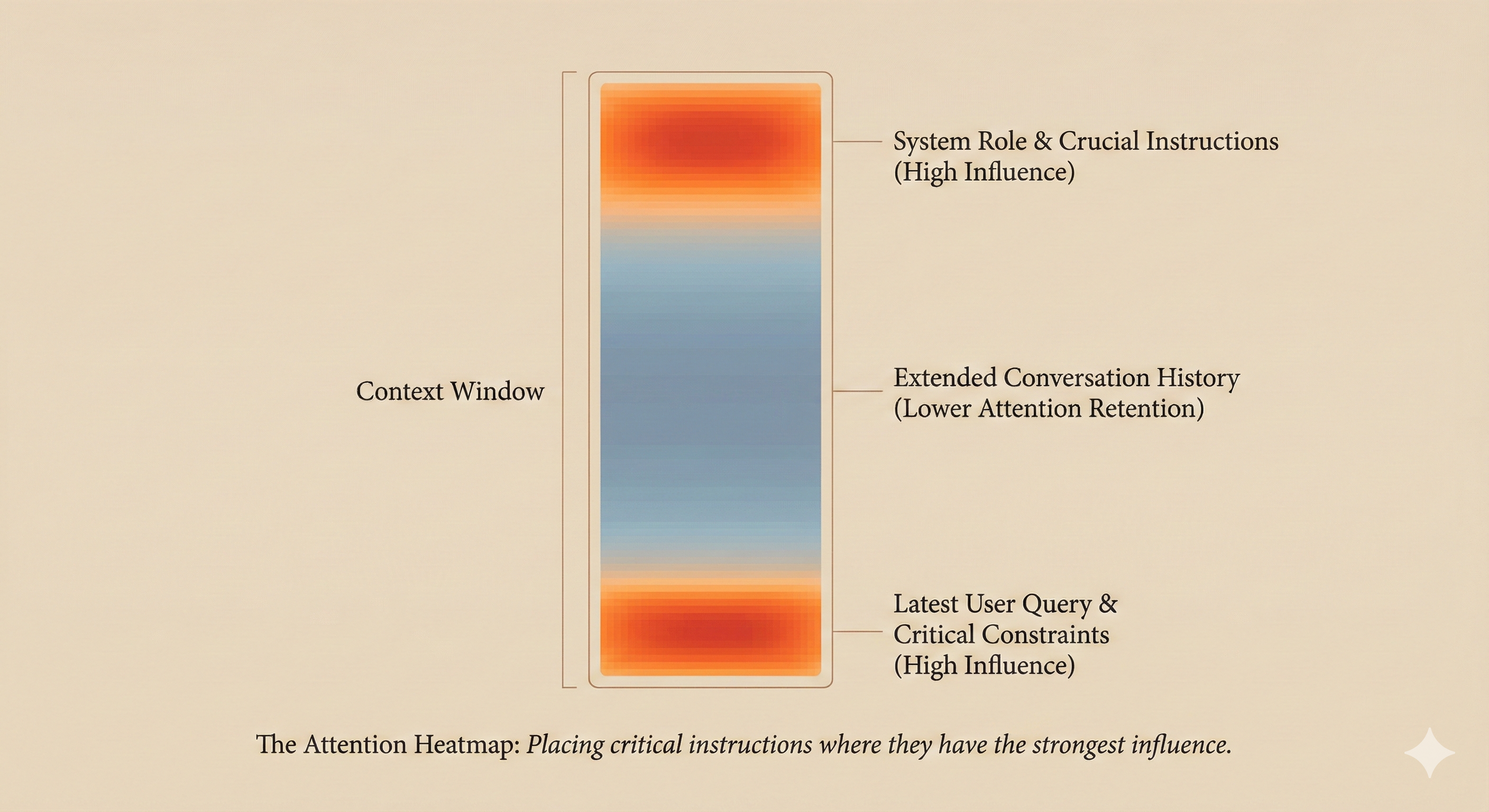

6. Put Instructions Where They’ll Be Followed

Research shows that models pay more attention to certain positions in the context window. Instructions at the very beginning (system prompt) and very end (near the user query) tend to have the strongest influence.

For critical instructions, consider stating them in both positions. As Microsoft’s Azure OpenAI documentation notes: “It’s worth experimenting with repeating the instructions at the end of the prompt and evaluating the impact.”

OpenAI’s GPT-4.1 guide concurs: “If you have long context in your prompt, ideally place your instructions at both the beginning and end of the provided context, as we found this to perform better than only above or below.”

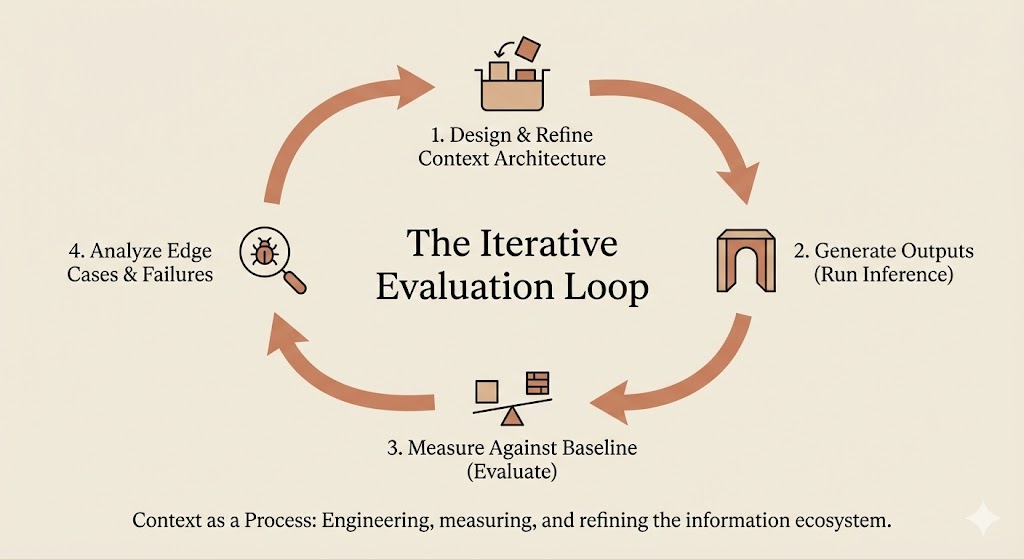

7. Build Evaluation Into Your Workflow

Prompt engineering isn’t a one-shot activity. It’s an iterative process that requires measurement.

Anthropic’s recommendation: “Establish a baseline. For positive and negative examples, run prompts using the current production configuration and record outputs as the baseline.”

Then systematically test changes against that baseline. The faster your evaluation loop runs, the more iterations you can make.

8. Separate System-Level Concerns from Task-Level Details

The emerging consensus, as articulated by PromptHub’s analysis, is that system messages should contain:

- Role and persona definition

- Behavioral guidelines and constraints

- Persistent rules that apply across all interactions

While user messages should contain:

- Specific task instructions

- Relevant context for this particular request

- Examples pertinent to the current query

This separation makes prompts more maintainable and easier to iterate on.

The Shift from Prompt Engineering to Context Engineering

The industry is experiencing a terminology shift that reflects a deeper conceptual evolution. “Prompt engineering” implied that the craft was primarily about writing clever instructions. “Context engineering” recognizes that we’re actually designing information architectures.

The shift was crystallized in mid-2025 when Tobi Lütke tweeted: “I really like the term ‘context engineering’ over prompt engineering. It describes the core skill better: the art of providing all the context for the task to be plausibly solvable by the LLM.”

Karpathy’s response amplified the concept: “Science because doing this right involves task descriptions and explanations, few shot examples, RAG, related (possibly multimodal) data, tools, state and history, compacting… Doing this well is highly non-trivial. And art because of the guiding intuition around LLM psychology.”

As LangChain’s analysis put it: “A common reason agentic systems don’t perform is they just don’t have the right context. LLMs cannot read minds—you need to give them the right information. Garbage in, garbage out.”

This isn’t just semantic games. The terminology shift signals a maturation in how we think about building with LLMs. We’re not trying to trick the model with magical incantations. We’re engineering systems that provide the right information, in the right format, at the right time.

The model is no longer the star of the show. It’s a critical component within a carefully designed system where every piece of information—every memory fragment, every tool description, every retrieved document—has been deliberately positioned to maximize results.

Practical Takeaways for Software Engineers

-

Audit your context window. Before optimizing individual prompts, understand what’s actually being sent to the model. Log the full request. You may be surprised by what’s consuming your token budget.

-

Invest in your system prompt architecture. This isn’t throwaway code. It’s infrastructure that affects every interaction. Version control it. Review it. Test it.

-

Build modular context loading. Don’t try to fit everything into one giant prompt. Design systems that load relevant context on demand.

-

Create evaluation datasets early. You can’t improve what you can’t measure. Build a suite of test cases that represent real usage, including edge cases.

-

Document your context decisions. Future you (and your team) will want to know why certain instructions were added. Context engineering decisions should be as well-documented as code architecture decisions.

-

Remember the attention budget. Every token you add has a cost—not just in API pricing, but in model attention. Be judicious.

-

Test at the boundaries. The model’s behavior at edge cases is where context engineering matters most. Focus your evaluation there.

Conclusion

The age of treating LLM prompting as an afterthought is over. Modern LLM applications succeed not because of clever one-liners, but because their architects have learned to orchestrate comprehensive information ecosystems around the model’s context window.

Context is king because context is all the model actually sees. Your system prompts, your skill files, your retrieved documents, your conversation history—this is the total reality available to the model at inference time. Everything else is invisible.

Understanding this isn’t just useful for writing better prompts. It’s essential for building AI systems that work reliably in production. The model’s intelligence is fixed at training time. The context you provide is the only lever you have at runtime.

Use it wisely.

References and Further Reading

Official Documentation:

- Anthropic: Effective Context Engineering for AI Agents

- Anthropic: Claude 4.x Prompting Best Practices

- OpenAI: GPT-4.1 Prompting Guide

- OpenAI: GPT-5 Prompting Guide

- Microsoft Azure: Prompt Engineering Techniques

- Google Developers: Context-Aware Multi-Agent Framework

Key Thought Leadership:

- Andrej Karpathy on Context Engineering (X/Twitter)

- Tobi Lütke on Context Engineering (X/Twitter)

- LangChain: The Rise of Context Engineering

- Simon Willison: Context Engineering

Research:

Community Resources: